Analysis of the state of ecological connectivity at the Pan-Amazon level (1985-2023)

PROTECTING CONNECTIVITY IN THE AMAZON TO ENSURE CLIMATE RESILIENCE AND THE FUTURE OF THE PLANET

COP30: THE AMAZON AS THE CENTER OF THE CRISIS AND THE CLIMATE SOLUTION

The Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG) and the North Amazon Alliance (ANA)—two regional networks working in the Amazon—have joined to develop collaborative studies on connectivity issues. In this site, you will find the results of the analysis that highlights the importance of a well-connected Amazon for biodiversity conservation, climate regulation, and global resilience.

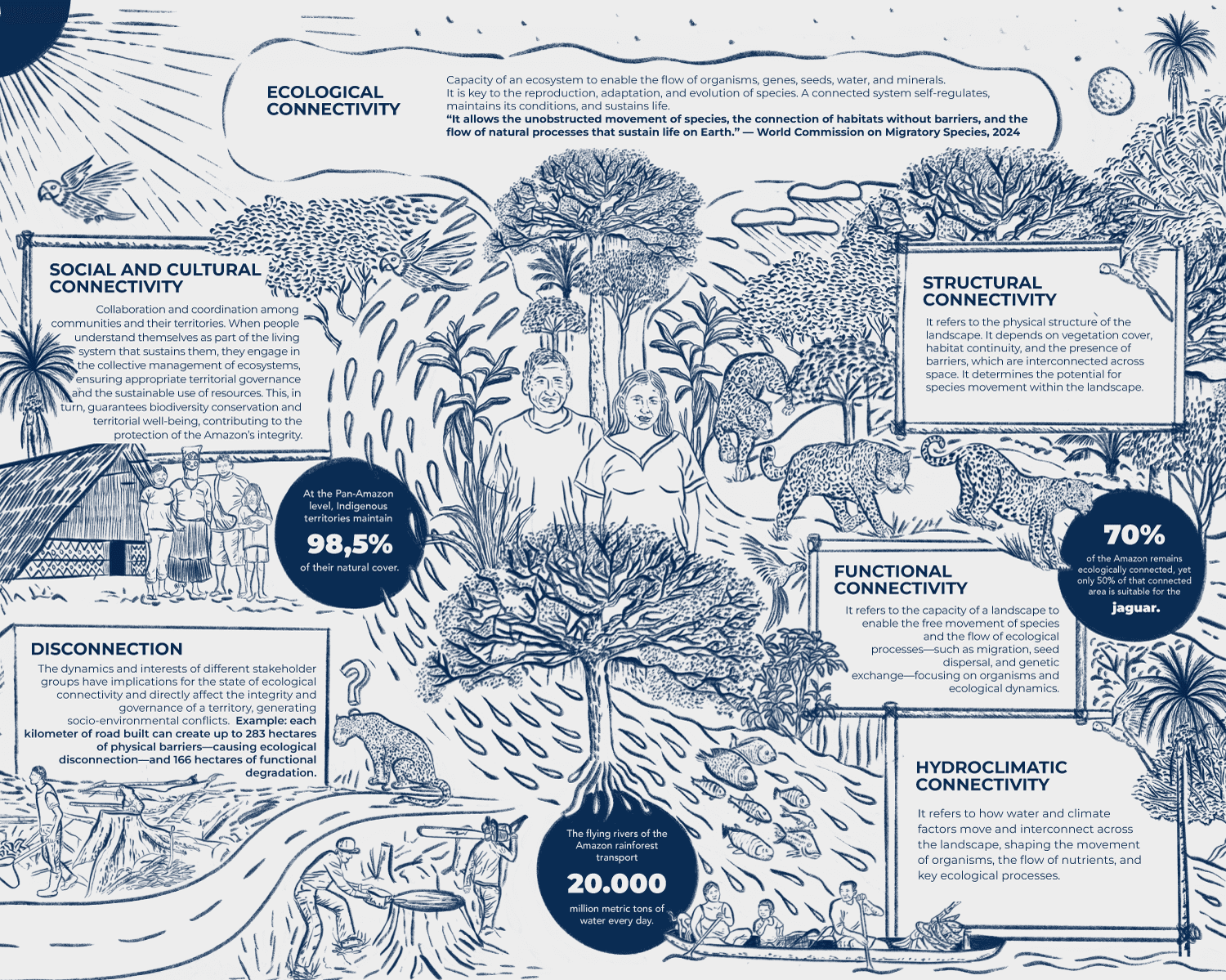

WHAT IS CONNECTIVITY?

Turn your device to see this infographic better.

HOW MUCH CONNECTIVITY HAS BEEN LOST AND WHAT IS AT RISK?

The Amazon is being increasingly fragmented each year. Activities related to agriculture, mining, and indiscriminate logging—among others—impact the forests and rivers, disrupting ecological connectivity.

Pan-Amazon GIF shows connectivity changes between 1985 and 2023

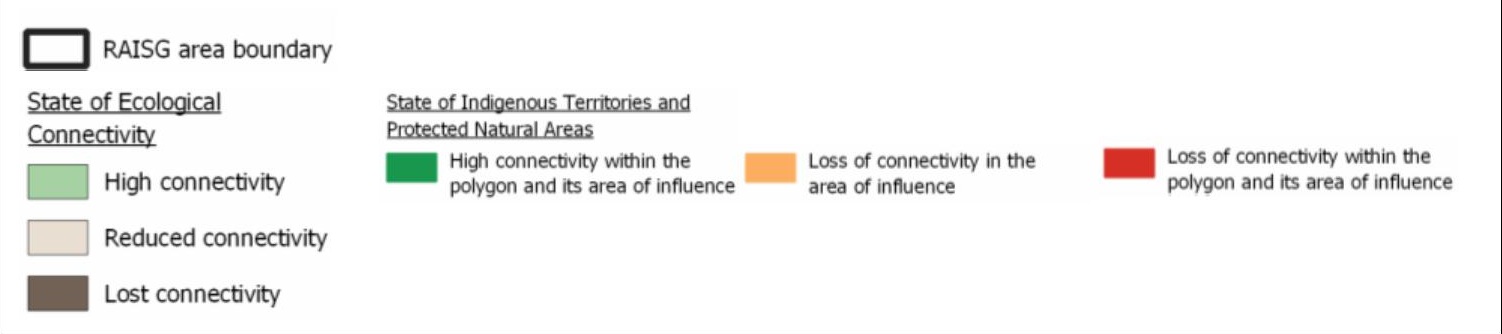

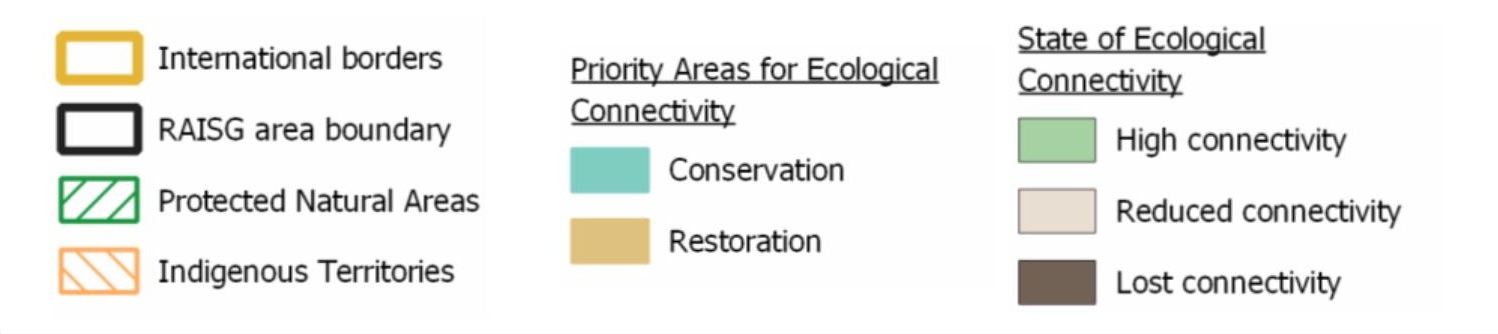

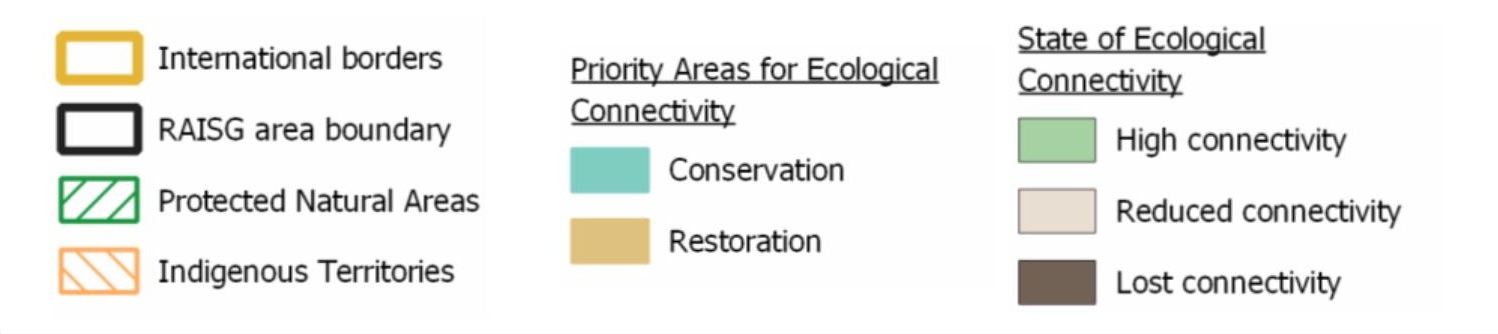

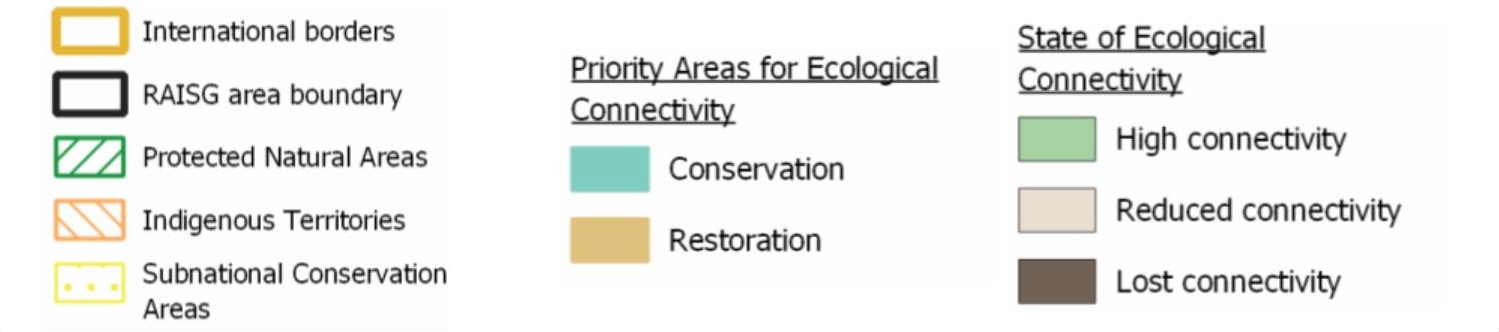

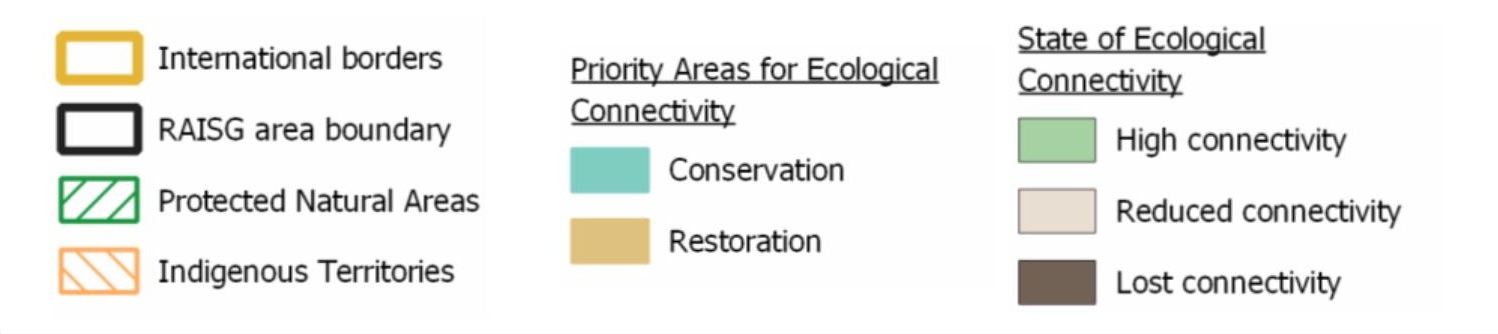

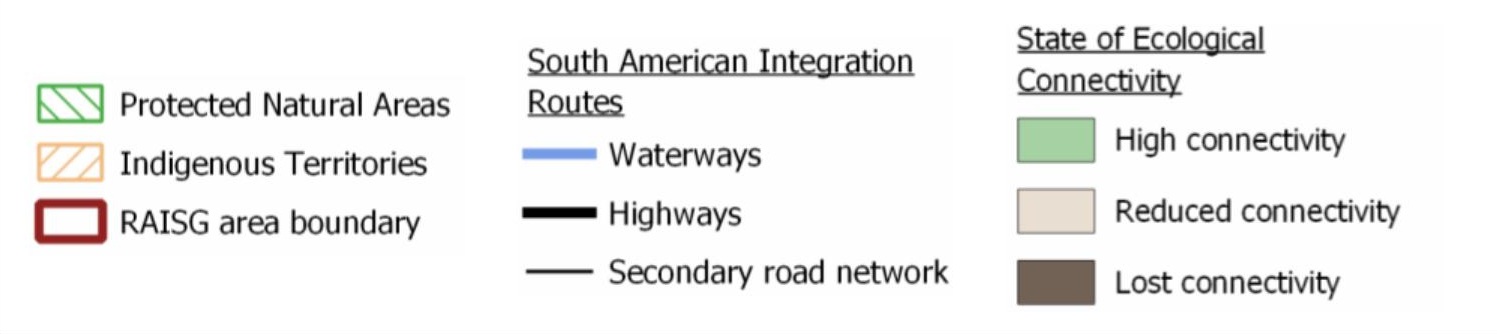

How to read this map:

The gray sections of the map represent areas where ecological connectivity has been lost, while the beige sections represent areas with reduced connectivity. These areas are increasing each year, while the green areas (representing areas of high connectivity) are decreasing.

By 2023:

of the Amazon lost ecological connectivity

(140,074,911 ha)

experienced a reduction in ecological connectivity

(104,814,109 ha)

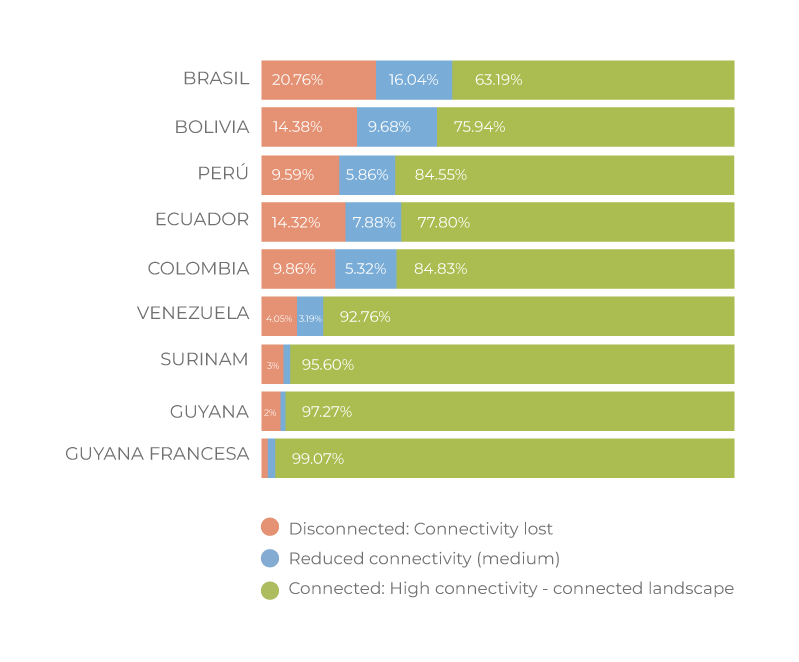

When we analyze the data by country, we see that Brazil has experienced the greatest loss or reduction in connectivity, while the Guyanas, Suriname, and Venezuela have the highest rates of connectivity.

When we analyze the data by country, we see that Brazil has experienced the greatest loss or reduction in connectivity, while the Guyanas, Suriname, and Venezuela have the highest rates of connectivity.

WHAT IS AT STAKE?

The loss of Amazonian connectivity threatens the functions and services of the most extensive and best-conserved tropical forest on the planet, as well as the largest and most diverse freshwater system. Much more is at stake than a territory: the world’s equilibrium is at risk.

–

The fundamental role of the Amazon in climate and water cycle regulation, at regional and global levels, as well as its role in storing carbon, triggering accelerated global warming

–

The resilience and biodiversity of the Amazon as a vital system for the countries of the region and for the planet.

–

The food, water and energy security for the 47 million people who live in the Amazon region, and for the population of other zones of the continent.

–

The health of Amazonian populations and beyond, in view of the propagation of pathogens, the appearance of zoonosis and the weakening of natural mechanisms for health regulation..

–

The sustenance of biocultural relations and the continuity of Indigenous and local knowledge systems, key for the resilience and the biodiversity of the basin, as well as practices that have been shown to be effective to maintain connectivity.

–

The effectiveness of national strategies of Indigenous Territories (IT) and Protected Natural Areas (PNA) to conserve ecosystems.

–

Compliance with international commitments and sustainable development frameworks.

–

Political stability, territorial governance and legal security in the face of the advance of illegal economies.

WHERE IS CONNECTIVITY MAINTAINED?

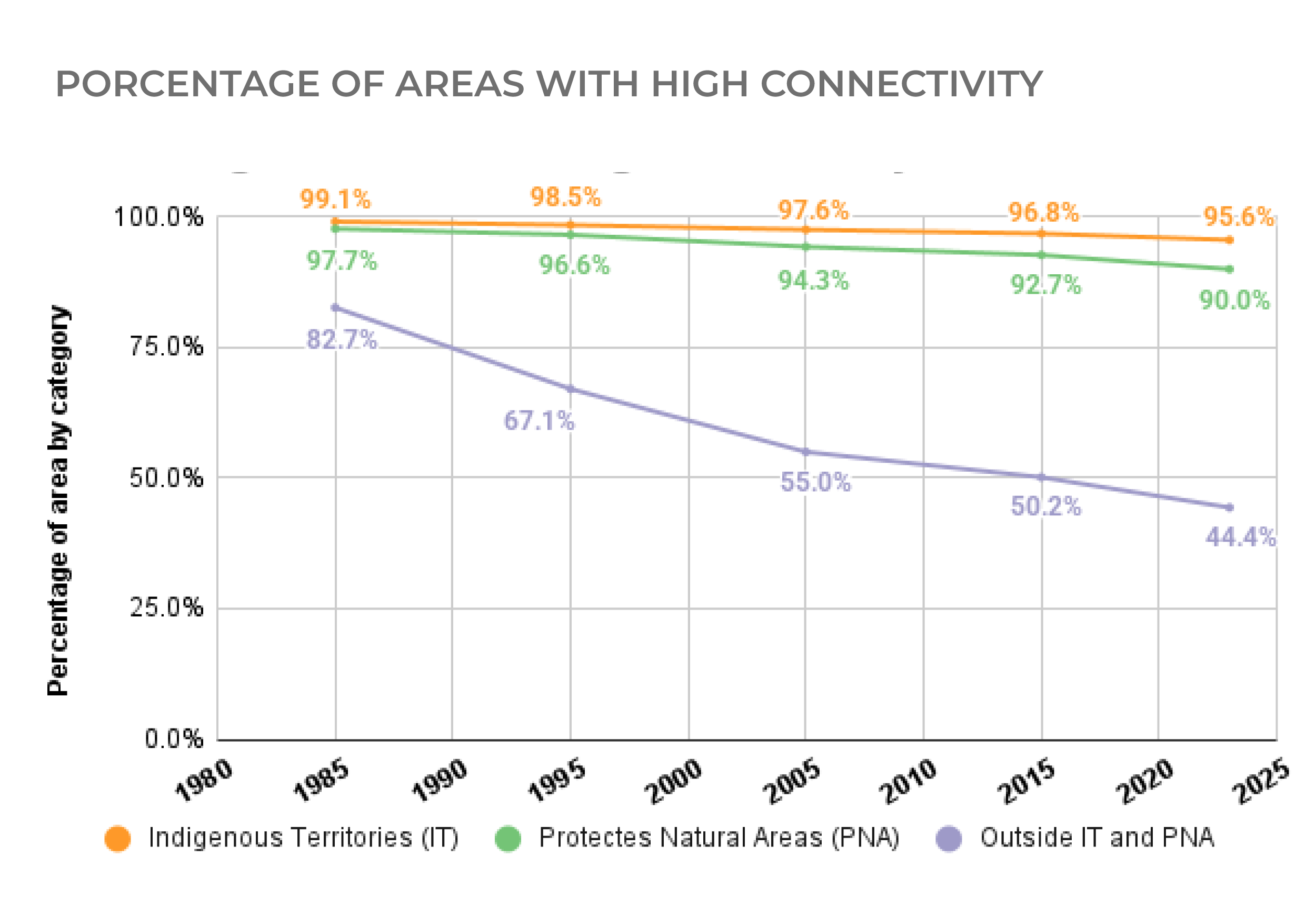

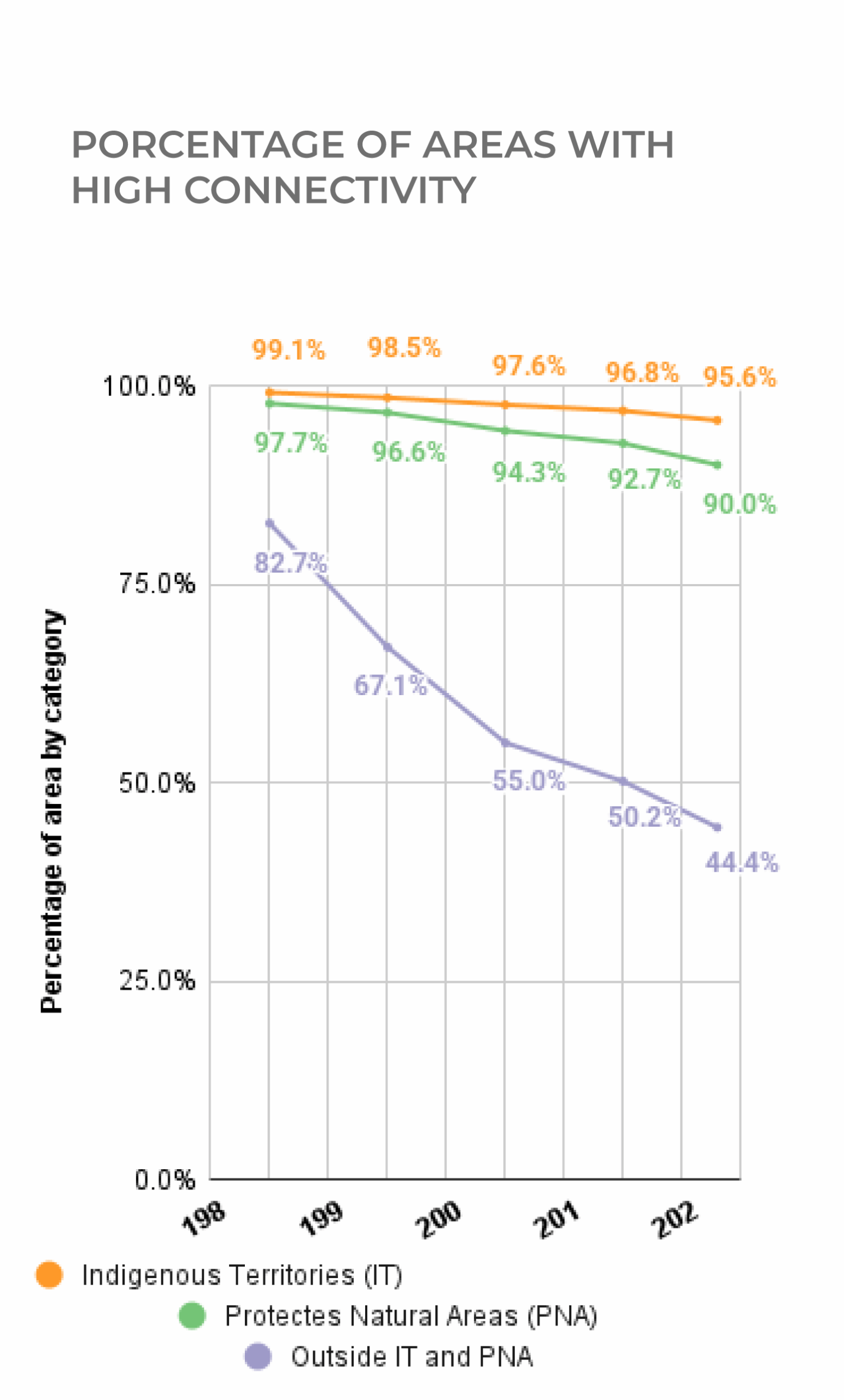

Indigenous Territories (IT) and Natural Protected Areas (NPA) ARE STRATEGIES to maintain connectivity in the Amazon.

ITs and PNAs maintain better connectivity than areas without any form of protection, but they are at risk of becoming disconnected from other forest areas and, consequently, losing their vitality.

Status of connectivity, Indigenous Territories, and Protected Natural Areas

Total area designated as NPA: 240,047,375.8 ha

Total area designated as IT: 193,135,651 ha

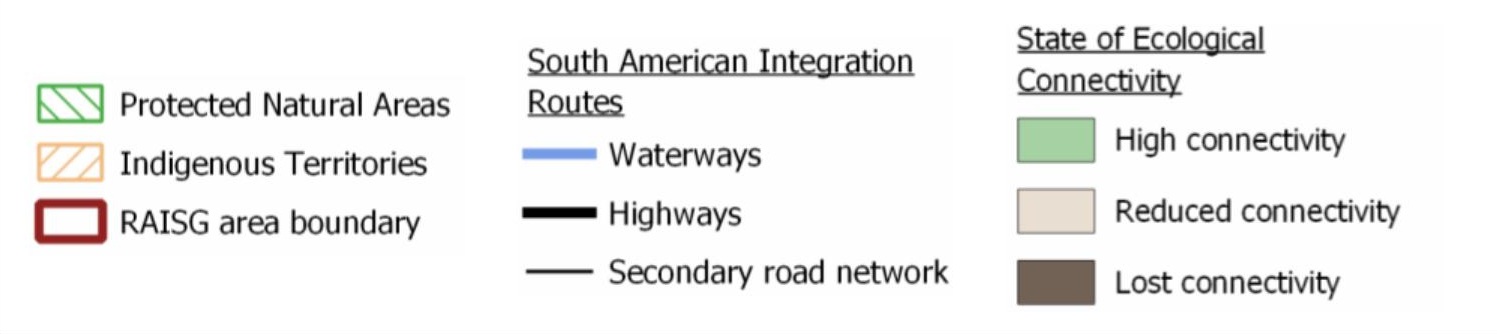

How to read this map:

Year after year, we witness the Amazon losing its connectivity. The areas in gray and beige, which indicate areas of lost and reduced connectivity, respectively, are encroaching upon the green areas that represent high connectivity. The loss and reduction of connectivity are most pronounced outside ITs (indicated by green stripes) and NPAs (indicated by orange stripes).

Nearly 50% of Pan-Amazon region is under some type of protection—designated Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) or Indigenous Territories (ITs)—but only 65.5% of these areas maintain high ecological connectivity both inside their limits and in their buffer zones.

By 2023, there was a loss of ecological connectivity inside these figures, or in their areas of influence as follows:

of PNAs

of ITs

Result: Ecological dynamics have been affected in 103 million hectares (23.8% of the area under some type of protection).

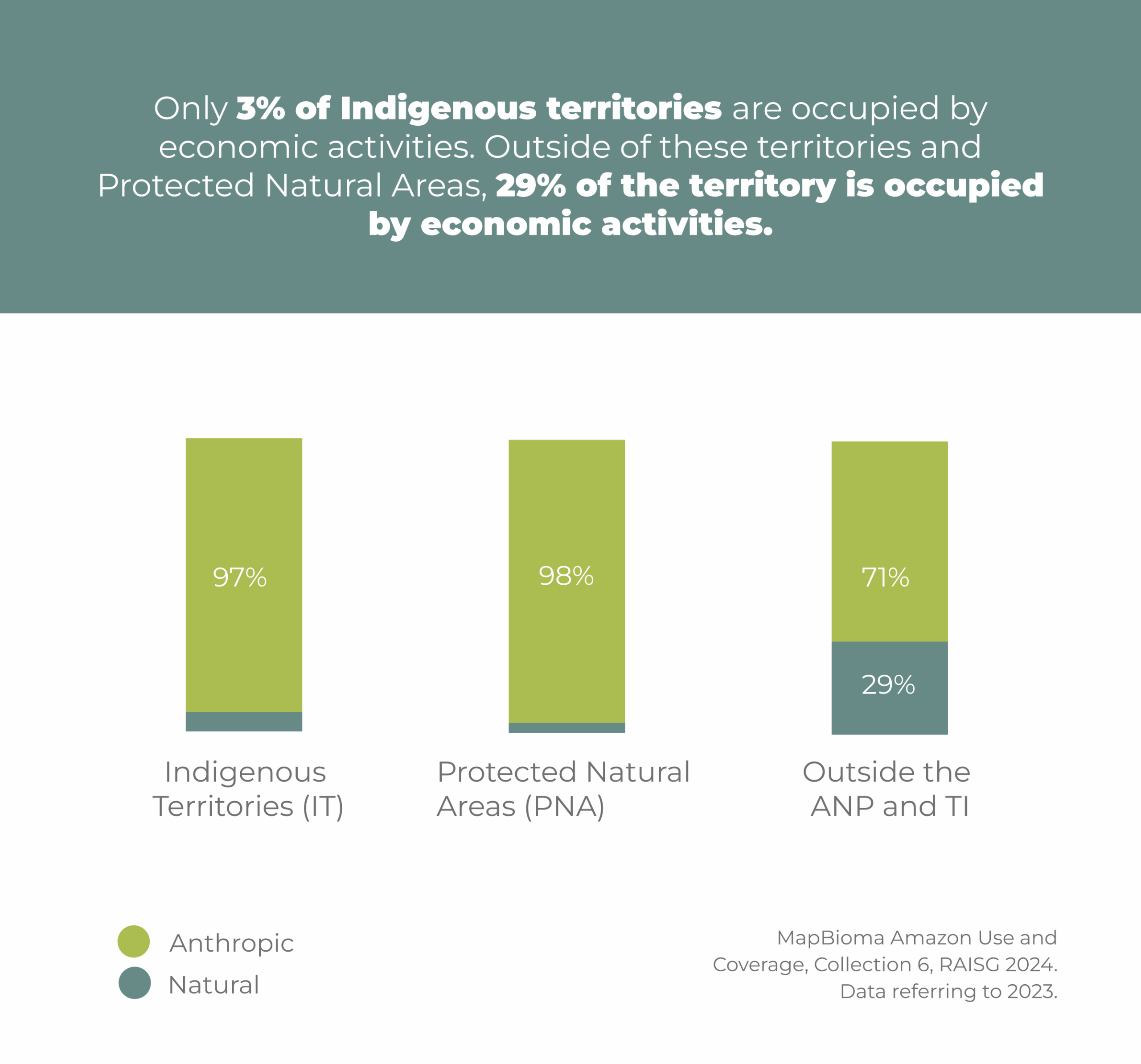

The expansion of economic activities disrupts the connectivity between Indigenous Territories and Natural Protected Areas and their surrounding landscapes. This loss of connectivity extends into Protected Areas, affecting connectivity within them. Meanwhile, Indigenous Territories manage to maintain their internal integrity, though they risk becoming isolated islands, disconnected from other areas of forest.

Indigenous Territories (ITs) are effective in maintaining connectivity. These knowledge and territorial governance systems preserve structural and functional connectivity across 93% of the area under this designation—more than 182 million hectares. However, they face a high risk of becoming isolated forests as they lose connectivity with neighboring forest areas. The traditional knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples—along with their community-based monitoring, control, and surveillance strategies to protect their territories—enable these areas to remain highly connected.

The loss of connectivity in Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) threatens the resilience of the forests. Connectivity loss even extends into these areas where conservation strategies have been implemented In fact, connectivity has been lost or reduced in approximately 22 million hectares—representing 10% of the total area under this designation.

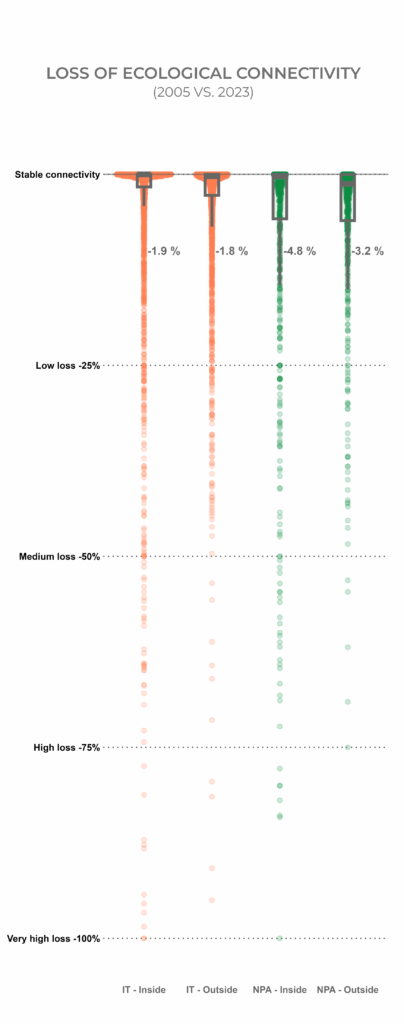

WHAT IS THE STATUS OF CONNECTIVITY IN INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES AND PROTECTED NATURAL AREAS?

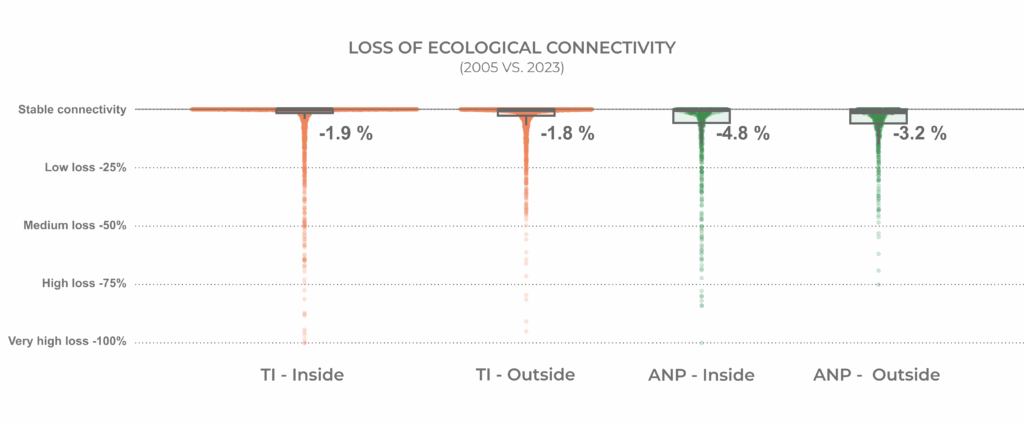

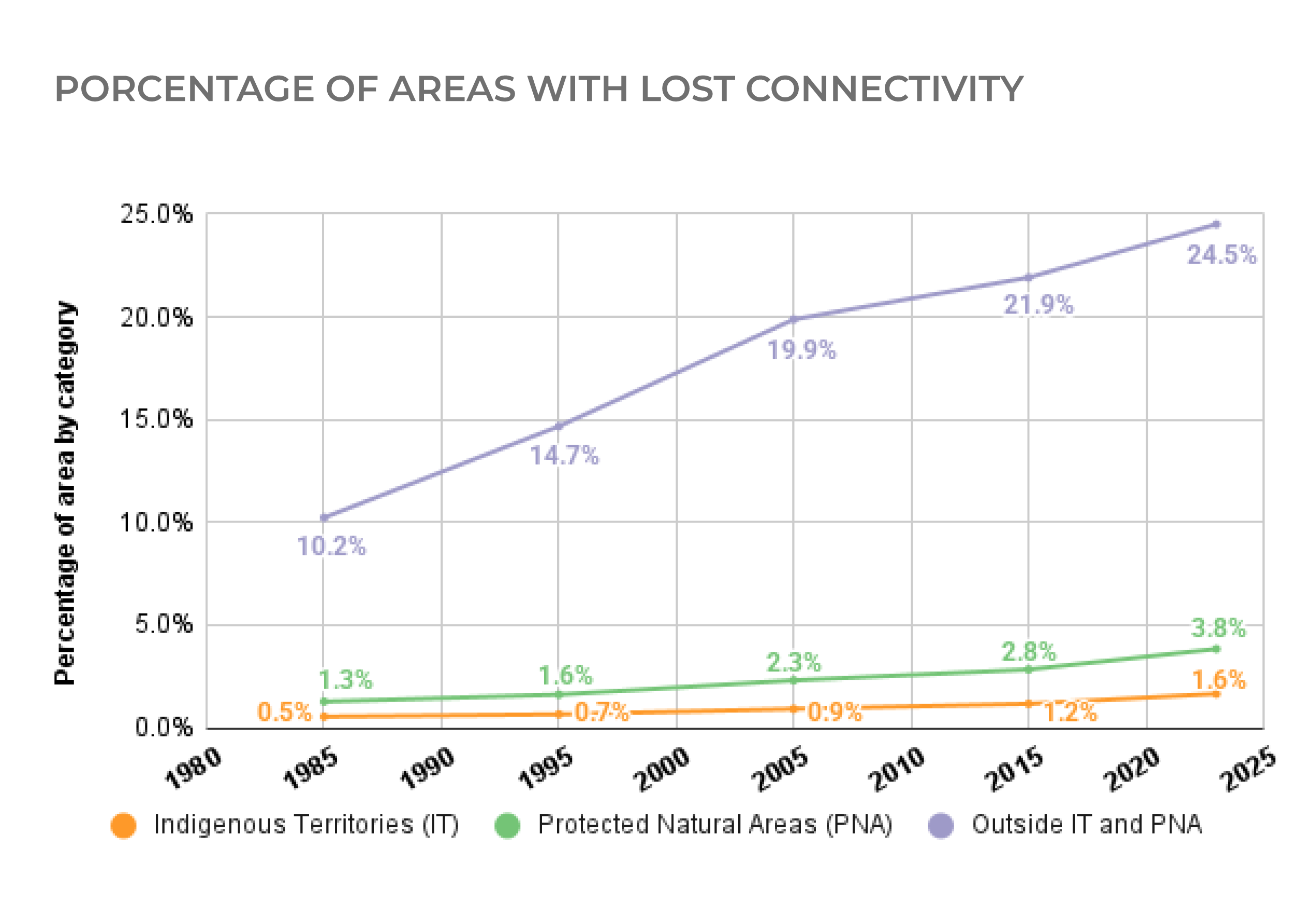

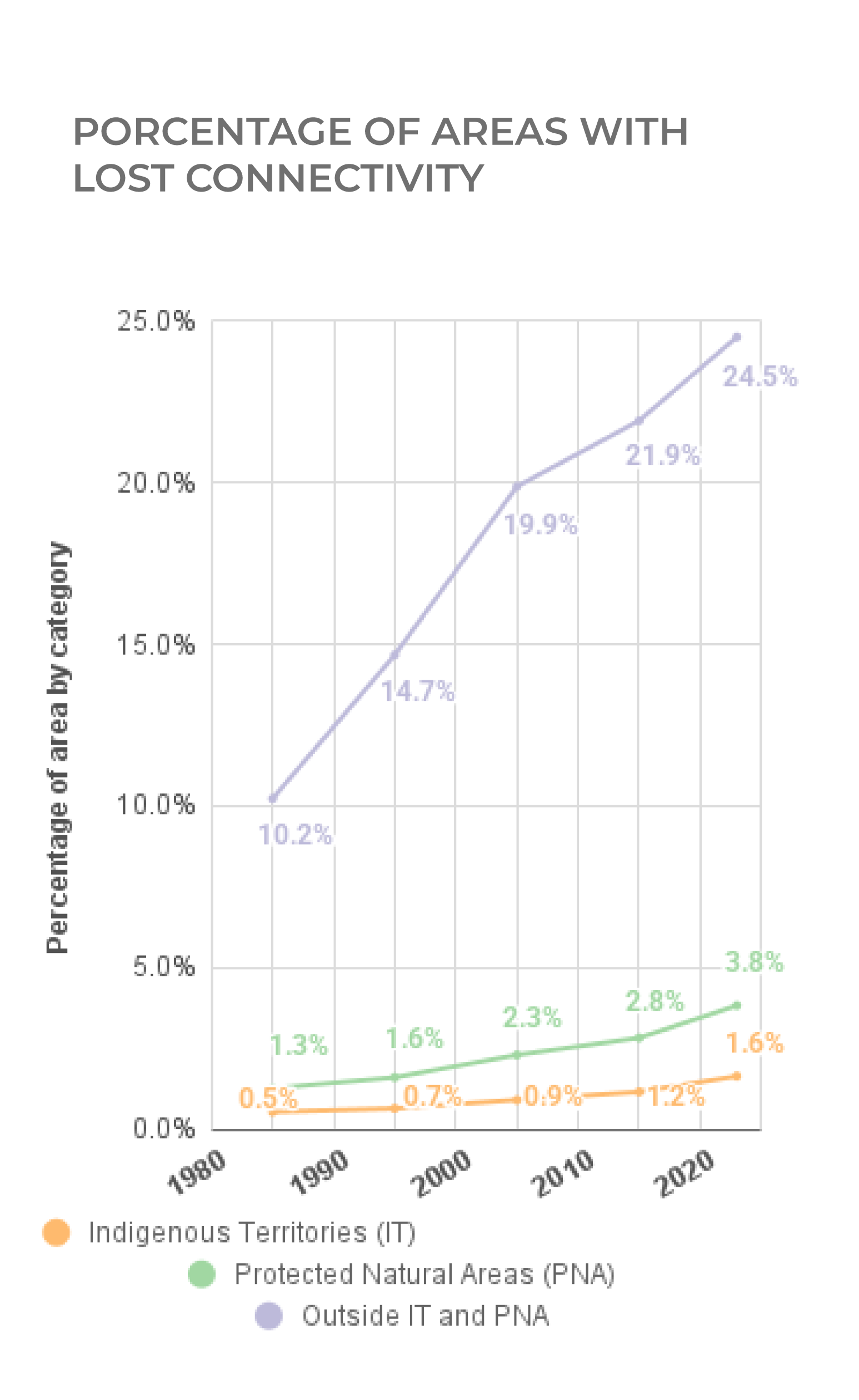

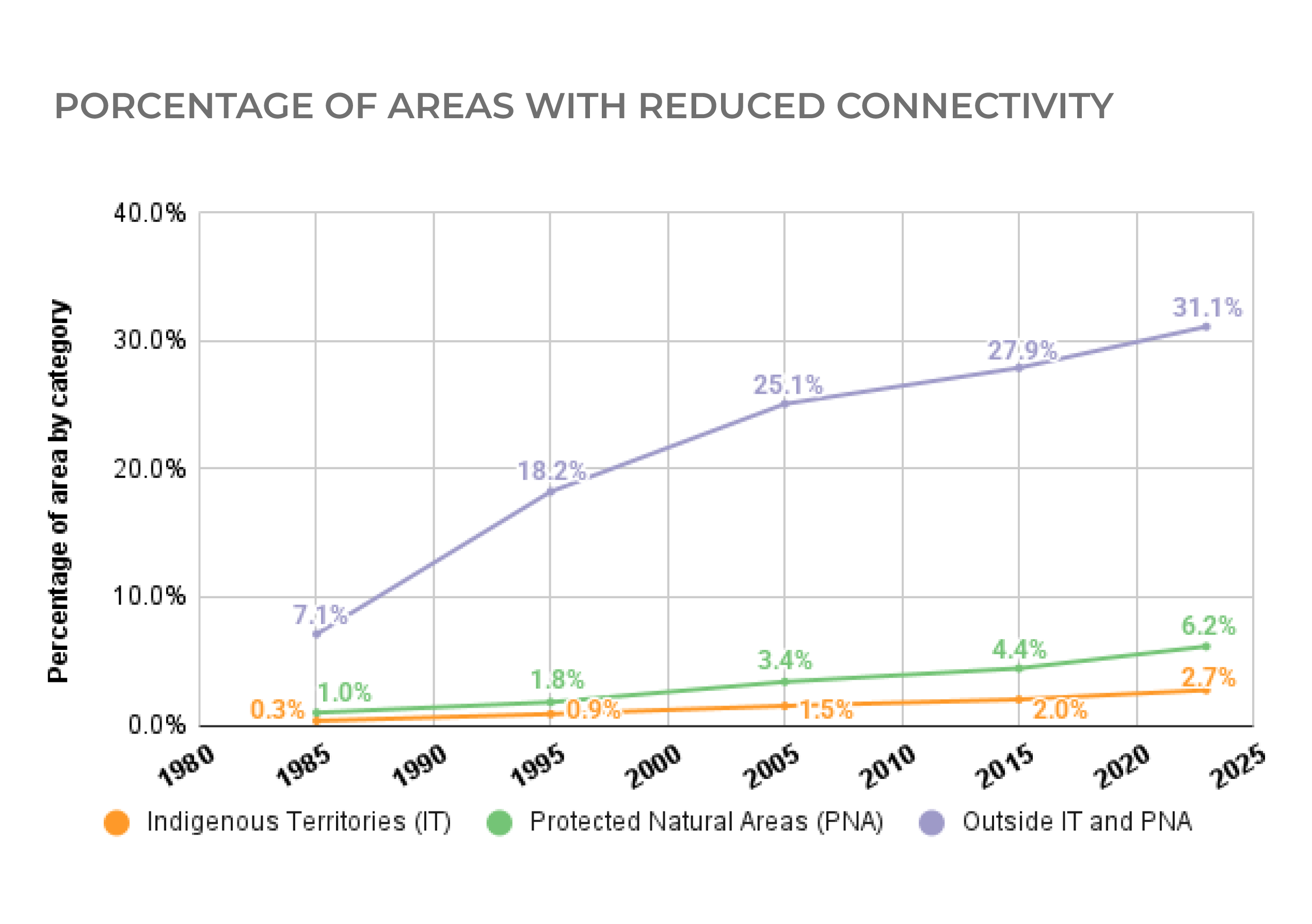

The loss of ecological connectivity is more pronounced in Natural Protected Areas than in Indigenous Territories.

The figure above shows the loss of ecological connectivity between 2005 and 2023. Each dot represents the percentage of connectivity loss for each Natural Protected Area (green) and Indigenous Territory (orange), both within its polygon and in the surrounding area. The grey boxes indicate where the largest number of NPAs and ITs are concentrated.

The results show that although a large proportion of NPAs and ITs maintain high internal ecological connectivity, the areas of influence of NPAs experience a lower proportion of high connectivity compared to those of ITs. This suggests greater vulnerability of NPAs regarding transformation processes and the loss of ecological integrity caused by socioeconomic activities, which reduces their resilience and adaptive capacity under global change scenarios.

The average percentage of connectivity loss is higher within NPAs than within ITs. Similarly, the loss outside the areas of influence is also greater in NPAs than in the case of ITs. In summary, the loss of ecological connectivity is more pronounced in Natural Protected Areas than in Indigenous Territories. The same is true for the areas of influence—or buffer zones—of NPAs compared to those of ITs.

INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES AND NATURAL PROTECTED AREAS ARE ALSO UNDER THREAT

Although Indigenous Territories and Natural Protected Areas generally maintain their forests, in some regions they are becoming islands surrounded by pastures, crops, mining operations, and roads, among others.

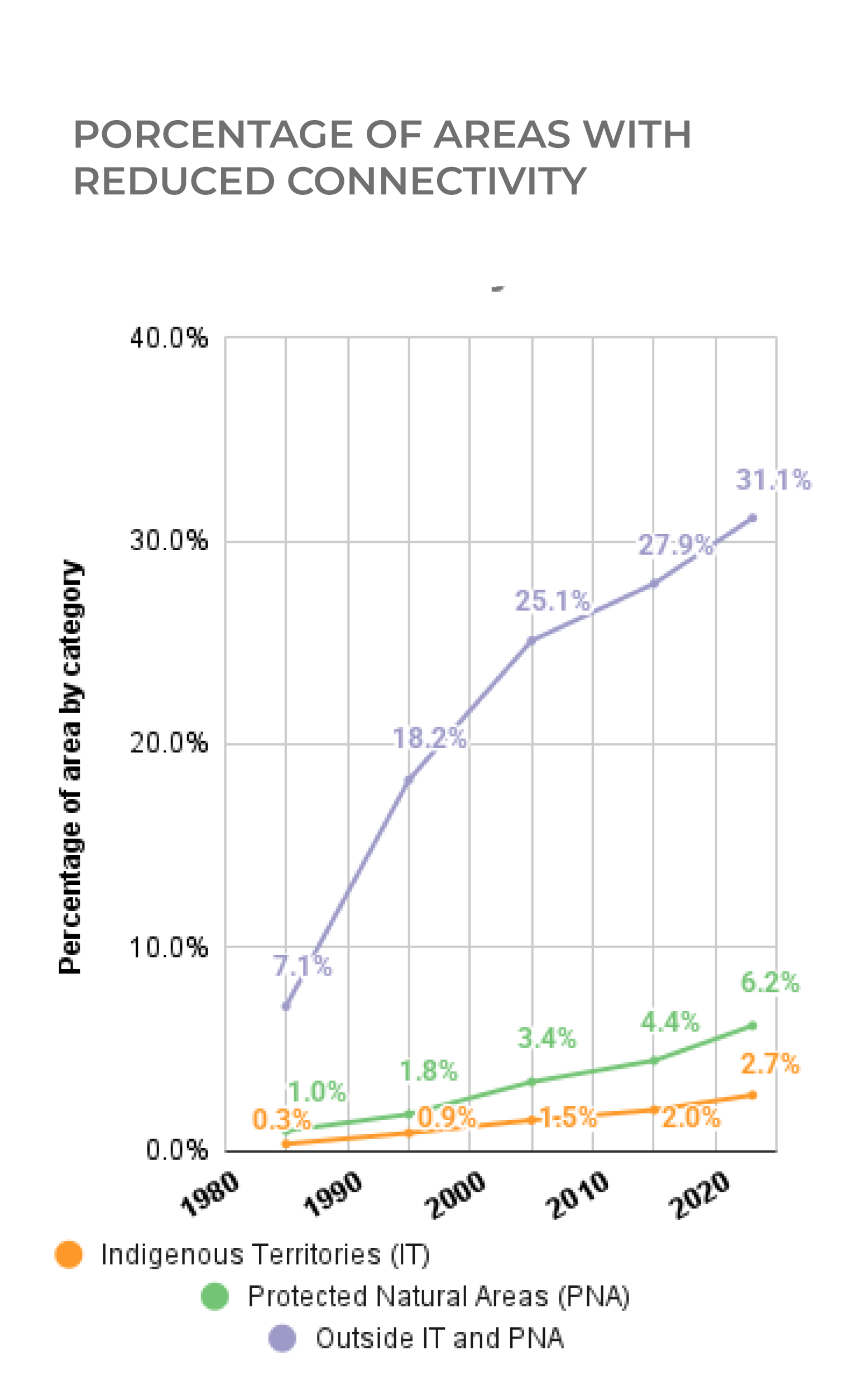

Over the past 38 years, both Indigenous Territories and Natural Protected Areas have shown a trend of declining connectivity with the surrounding forests.

This growing isolation not only increases the vulnerability of these territories but also of the entire region. As a result, the Amazon is losing its capacity to regulate climate and water cycles at regional and global scales.

Connectivity loss in ITs and PNAs

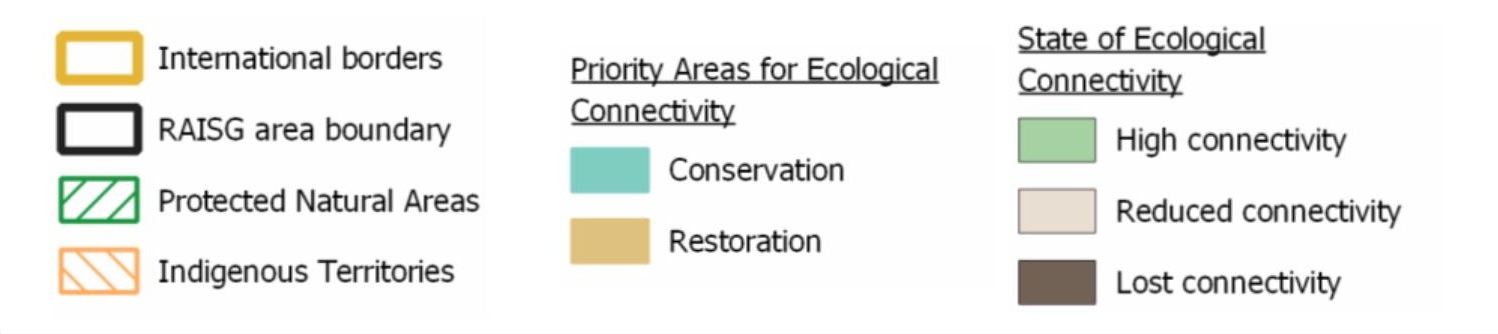

How to read this map:

In this map, the green sections correspond to conservation areas where ecological connectivity remains high, both within the interior and in the area of influence, or buffer zone. The orange sections indicate areas where internal ecological connectivity is still high, but a reduction or loss of connectivity associated with economic activities is observed in the buffer zone. Finally, the red sections represent management units where the transformation of natural cover into anthropogenic cover has been so intense that it has fragmented the landscape, resulting in the loss or significant reduction of ecological connectivity.

The area of influence of Indigenous Territories and Natural Protected Areas is fundamental to identify the increasing pressures faced by these territories. Therefore, the level of ecological connectivity within each area, as well as in its buffer zone, was analyzed both independently and in relation to each other.

For nearly 40 years, the reduction or loss of ecological connectivity within Indigenous Territories and Protected Natural Areas has remained below 10% in both cases.

In contrast, outside these conservation areas, the rate of change in ecological connectivity has been much higher, indicating a reduction or loss across more than 169 million hectares (38.3%) compared to the conditions in 1985.

By 2023, the loss of ecological connectivity exceeded 24% (63,086,368 ha), while a partial reduction was observed in 31% (106,124,751 ha) of the territory outside Indigenous Territories and Protected Natural Areas throughout the Pan-Amazon region.

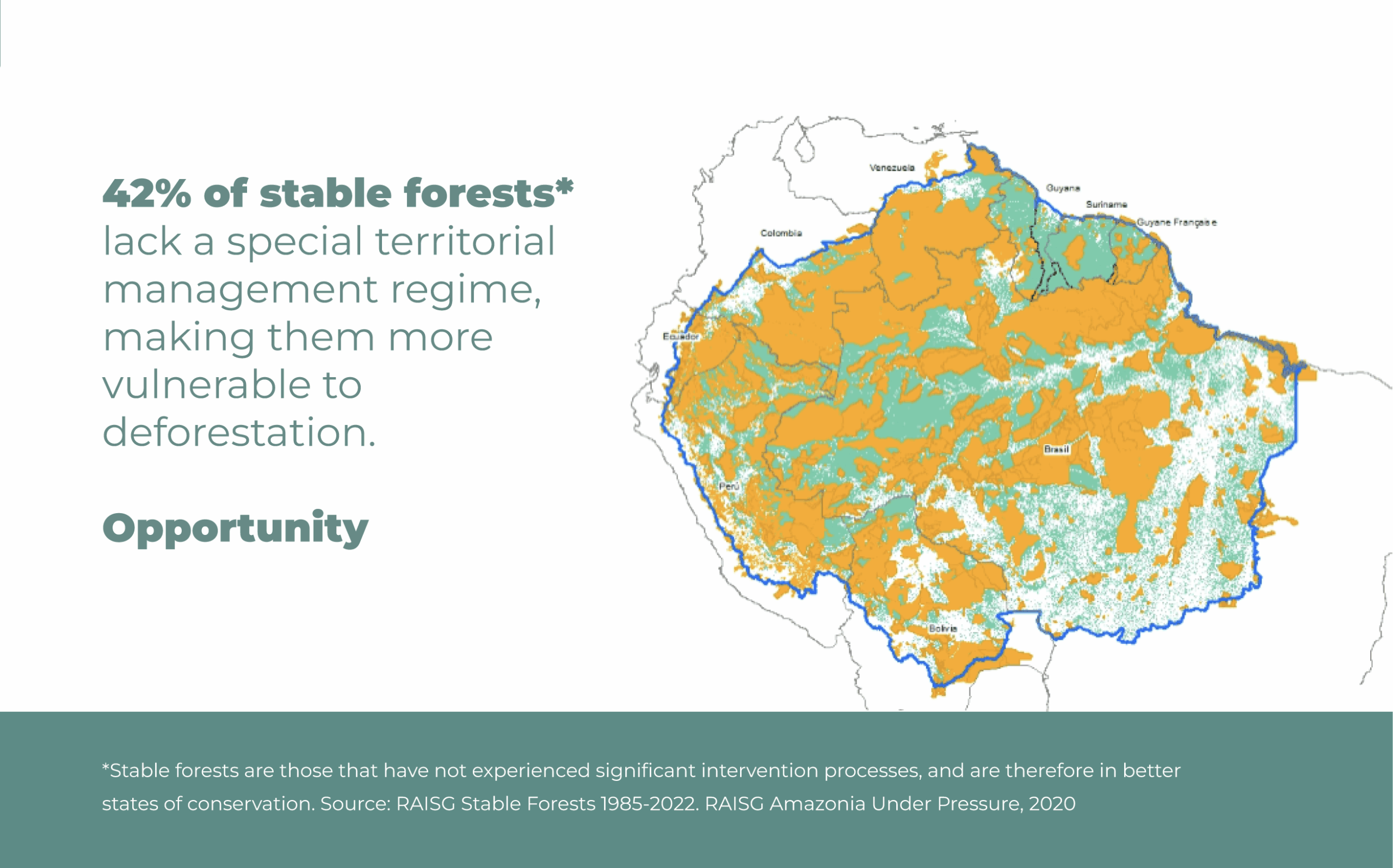

These areas help ensure that connectivity is maintained. Approximately 42% of the Amazon’s stable forests that are not under any of these categories are at risk, due to increasing illegal activities.

An innovative methodology to maintain connectivity and prioritize restoration and conservation actions in strategic regions:

Which areas should be prioritized, and based on what criteria?

It is possible to reconnect areas that are becoming disconnected through restoration efforts in priority areas, while also ensuring the conservation of well-connected areas.

This methodology for land planning developed from a connectivity perspective, is an innovative contribution to decision-making, as it provides a framework for prioritizing areas for restoration.

Isolated ITs and PNAs, as well as priority areas for conservation and restoration

Thus, this study provides a land planning framework to identify priority areas where urgent measures are needed in order to ensure connectivity. Some of these measures include identifying corridors—either between well-preserved patches of forest to enable the movement of species, or between different protected areas or conservation categories— in order to form and consolidate priority areas for connectivity.

These corridors and priority areas for connectivity are essential for ensuring adaptation to changing scenarios that unfold from the climate crisis.

This methodology focuses on addressing two types of scenarios in order to establish clear criteria to identifypriority areas for connectivity:

A.

Landscapes with a high risk of connectivity loss

B.

Well-preserved landscapes that maintain connectivity and are therefore important for safeguarding it at a broader scale

The methodology allows to identify specific areas that effectively support the mobility of large mammals through a concentrated flow analysis. For species with a large body mass, these areas should be as wide and short as possible—approximately six kilometers. By overlaying criteria that combine ecological factors with social factors—such as roads, mining, and water-use corridors—it becomes possible to highlight the implications of human activities not only on the physical landscape but also on decision-making processes related to ecological connectivity. Identifying high-priority areas with strong connectivity—as well as restricted areas with reduced connectivity—enables the drafting of concrete recommendations for decision-makers and area-prioritizing proposals. Although connectivity can be restored through ecological restoration, it is a costly and a long-term process; therefore, it is more effective to safeguard and maintain healthy, standing forests as the main hubs for local connectivity strategies.

This approach is particularly relevant for decision-making at the local level, as land planning from a connectivity perspective enables timely actions to ensure the functional viability and vitality of ecosystems. It also facilitates the identification of high-connectivity areas that can serve as bridges between zones where connectivity is being lost, as well as areas requiring urgent restoration actions to prevent further disconnection. For this reason, specific illustrative cases are presented below, by country.

The case study analyses—validated through a methodological process involving territorial teams working directly on the ground in each area—confirm that the applied methodology is both highly accurate and replicable, as well as scalable.

CASE STUDIES IN SPECIFIC TERRITORIES: ZONING FROM A CONNECTIVITY PERSPECTIVE

Case studies by country:

Bolivia - Lomerío and Monte Verde case, Chiquitana region of Santa Cruz:

A TIOC (Indigenous Originary Peasant Territory or Territorio Indígena Originario Campesino in Spanish) is the name given to Indigenous Territories as recognized in the land planning within Bolivia’s legal framework. TIOCs represent spaces where Indigenous Peoples and Nations exercise autonomy, self-government, and territorial management in accordance with their own norms, institutions, and forms of organization. The Lomerío TIOC, inhabited by the Monkoxi people, and the Monte Verde TIOC—which still conserves extensive forested areas—are both located in the Chiquitana region of Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Although Lomerío is fragmented, it preserves remnants of dry forest with significant restoration potential, while Monte Verde has been severely affected by recent fires that have weakened its ecological functions.

Both territories are part of a mosaic of strategic ecosystems that connect dry forests, savannas, and Amazon transition areas.

The ecological connectivity between these territories and nearby protected areas is fundamental for the mobility of key species such as the jaguar, the anta (known elsewhere as the tapir), and the peccary, as well as for the natural regeneration of flora in Tropical Important Plant Areas (TIPAs). However, these corridors face increasing threats from agricultural expansion, forest fires, and extractive activities that fragment the landscape and endanger both biodiversity and traditional livelihoods.

In response to these challenges, both TIOCs promote community-based monitoring and support conservation efforts, such as the jaguar conservation initiative in Monte Verde. They are also committed to sustainable land management models based on Indigenous knowledge systems. In this context, the strengthening of biocultural corridors—which combine ecological restoration with cultural revitalization—emerges as a key strategy for regional sustainability and for the defense of Indigenous territories in the face of climate change and extractive pressures.

Brazil: The Biodiversity Corridor and the Challenge of the Xingu Headwaters

The Xingu Socio-Environmental Diversity Corridor is one of the most critical conservation frontiers on the planet, serving as a vital link between the Amazon and Cerrado biomes. Its integrity is essential for maintaining large-scale ecological processes, ensuring gene flow and the movement of key species such as the jaguar. However, the Xingu headwaters region, where the rivers originate, is under intense pressure from agricultural expansion, leading to severe landscape fragmentation.

This accelerated fragmentation in the headwaters poses a direct threat to the water and biological security of the entire corridor, as deforestation undermines the functionality of the ecological network.

The connectivity study reveals that the Xingu works through “arteries” (preferential corridors) and “bottlenecks” (vulnerable points), both vital for the circulation of life. The analysis therefore aims to accurately map these areas, differentiating forest remnants according to their vital importance for the survival and resilience of the entire ecosystem.

The results provide a Strategic Matrix for decision-making, identifying areas with High-Performance Environmental Assets and Critical Restoration Areas (CRAs)—liabilities that constrain connectivity. As such, the study offers a roadmap for directing conservation and restoration investments in a financial and ecological strategic way. It is important to emphasize that the methodology applied is highly replicable and scalable, opening the possibility for its implementation throughout the Xingu Basin. This approach transforms legal compliance into meaningful ecological gains and strengthens the long-term sustainability of the entire basin.

Colombia: Ecological connectivity between the Serranía del Chiribiquete National Park and the Macarena Special Management Area (AMEM)

The ecological connectivity between the Serranía del Chiribiquete National Park and the Macarena Special Management Area (AMEM in Spanish)—which encompasses National Parks, Integrated Management Districts, Forest Reserves, Indigenous Territories, and Campesino Reserves—is fundamental for the maintenance of the connection between the Amazon, Andes, and Orinoco biomes. These areas also hold high socio-cultural significance, as they are territories of great importance for numerous campesino and Indigenous communities.

Despite their ecological and cultural value, the departments of Caquetá and Guaviare are experiencing the rapid expansion of economic activities that degrade ecosystems and affect essential services that support life.

This trend has accelerated in the period following the armed conflict (after 2017), placing these highly connected natural areas at risk of disappearing, and losing the ecological link between the Andes and the Amazon.

Based on the Pan-Amazon Ecological Connectivity Study conducted by RAISG and on the land planning process for the conservation and restoration of ecological connectivity, key areas were identified that enable the continuous flow of species and habitat connectivity within this crucial junction between the Andes, the Orinoco, and the Amazon. These areas are located mainly north of Serranía de Chiribiquete National Park—the gateway to the tropical rainforests —on the eastern side of Sierra de La Macarena National Park, and north of Tinigua and Cordillera de Los Picachos National Parks, a transitional area between the high Andes and the foothill forests.

Ecuador: Andean-Amazonian Transition

Ecological connectivity between the Andes Mountains and the Amazon is fundamental for the preservation of ecosystem functionality and regional climate stability.

These two biomes are not only geographically linked, but also maintain a critical interdependence: their connection enables the flow of nutrients, species, genes, and ecosystem services, as well as the regulation of water and climate—processes that are essential for the resilience of both biomes.

The loss of this connectivity compromises the health of both systems, affecting biodiversity, local livelihoods, and their capacity to adapt to climate change.

In Ecuador’s Andes-Amazon region, the identified corridors include priority areas for conservation and restoration that function as transition areas between the ecosystems of the foothills of the Andes and the valleys of the Amazon. These areas face increasing pressures that threaten their ecological connectivity, primarily due to the expansion of road infrastructure, the expansion of the agricultural frontier, and the increase in extractive activities. Moreover, these zones overlap with the territories of several Indigenous nationalities, such as the Cofán, Shuar, Kichwa, and Secoya, whose ancestral land management practices serve as key pillars of both cultural and ecological connectivity. Their knowledge systems embody sustainable land stewardship deeply interrelated with nature, making the preservation of these practices and ways of life essential to ensure the socio-ecological resilience of these corridors.

Significant progress has been made at the national level to protect natural ecosystems and maintain ecological connectivity within the Andean region. However, it is equally important to highlight the initiatives led by subnational governments, in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, to maintain and strengthen ecological connectivity between these two biomes.

Peru: Kakataibo Indigenous Territories in the central jungle of Peru, Huanuco and Ucayali

The Kakataibo Indigenous Territories, located in the transition area between the Amazon and the Andean highlands, encompass parts of several identified corridors and extend across the basins of the Aguaytía, San Alejandro, Zungaruyacu, and Pachitea rivers—tributaries of the Ucayali. These areas reveal an urgent need to restore the areas about to lose connection (restoration tiles), which still function as bridges between Indigenous territories, nearby conservation areas, and Andean-Amazonian transition ecosystems.

These areas are vital for the mobility of the otorongo (jaguar, Panthera onca), the huangana (Tayassu pecari), and the choro monkey (Lagothrix lagotricha), sustaining key ecological processes like the regeneration of flora.

The restoration of these areas is a priority in the face of increasing pressure from agriculture and deforestation, as it ensures both ecological and cultural resilience—safeguarding the livelihoods and traditional practices of the Kakataibo people and other Indigenous communities in the region.

Additionally, this area is home to Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact (PIACI in Spanish), which is why legal protection has been requested for these areas as indigenous reserves.

Venezuela: Case of the tepuis as islands for ecological connectivity between natural and created barriers

In the extreme north of the Amazon, the Guiana Shield is one of the oldest and most remarkable landscapes on the planet. Its tepui formations—abrupt sandstone and quartzite plateaus rising between 1,500 and 3,000 meters above sea level—act as natural barriers within the otherwise continuous Amazon forest system. These formations constitute the Pantepui Biogeographic Province, an “archipelago” of discontinuous plateaus whose geographic separation has driven speciation processes. These biogeographic “islands” have fostered high levels of endemism and ecological differentiation, creating micro-ecosystems where life has evolved in isolation for millions of years.

Although their structure limits the mobility of some species between peaks and valleys, these systems also maintain altitudinal corridors that facilitate species adaptation to climate change and sustain the functional connection between the Amazon rainforest and the mountain ecosystems of the Guiana Shield.

However, beyond natural barriers, anthropogenic barriers now fragment ecological connectivity. In Venezuela, hydroelectric dams, mining expansion, and infrastructure associated with the Orinoco Mining Arc have significantly transformed the landscape. These alterations disrupt water flows, interfere with wildlife corridors, and degrade areas that once served as connecting areas between watersheds.

The connectivity of the Guiana Shield—key to the ecological and climatic stability of the northern Amazon—is thus strained between the natural barriers that structure diversity and the human barriers that fracture it.

Current species distributions are being affected by global warming (with a projected temperature increase of 2-4°C by 2100), posing a critical conservation challenge. The steep thermal gradient suggests that species sensitive to low temperatures will need to move upslope between 500 and 700 meters to find suitable conditions (Safont et al. 2014). However, most tepuis do not provide sufficient elevation, meaning that the long-term persistence of these ecosystems will depend on refuge strategies and mitigation of climate change impacts.

Given this scenario, conservation efforts should prioritize the maintenance of the functional corridors that still connect tepuis, savannas, and lowland forests, while promoting ecological restoration in areas affected by dams or mining. This approach requires the integration of scientific and local knowledge to protect the ecological and cultural flows that make this region one of the most extraordinary hubs of Amazonian connectivity.

Why do roads that connect markets fragment forests?

Currently, more than 175,000 km of roads have been built across the Pan-Amazon region, of which over 14,000 km cut through the interior of Protected Natural Areas (PNAs) and nearly 11,000 km pass through Indigenous Territories (ITs).

The regional integration road project represents a major threat to the Amazon, as projections estimate that more than 4,900 km of planned roads will traverse natural habitats such as forests and grasslands—including 1,255 km that would impact the region’s best-conserved forests (stable forests, according to RAISG). It is further estimated that these projected roads will overlap with more than 12,000 km of areas of high ecological connectivity.

Roads that connect markets cannot disconnect forests. Road, rail, and waterway projects across the region— intended to reduce shipping costs from South America to other continents—have intensified in recent years. Yet, the construction of each kilometer of road creates, on average, up to 310 hectares of physical barriers (connectivity loss) and 232 hectares of functionally degraded areas (reduced connectivity).

Roads are among the main drivers of deforestation and facilitate the expansion of economic activities, leading to growing ecological disconnection.

To illustrate this impact, this study examines two specific cases in Brazil:

Xingú Case Study

This study found a significant increase in road development in the western sector of the Xingu, with approximately 41,598 km of roads built by 2023. This represents a 243.8% increase compared to 1985, when 29,501 km of roads had been constructed. On average, for each kilometer of road built in this sector, 490.4 hectares of ecological connectivity are lost and 396.9 hectares experience reduced connectivity.

Porto Velho Case Study

For the road section between Porto Velho and Rio Branco, there were 33,009 km of roads by 2023—an increase of 474.3% (or 27,263 km) since 1985. The study found that, for every kilometer of road built in this sector, an average of 129.8 hectares of ecological connectivity are lost and 66.9 hectares are reduced.

HOW TO PROTECT AMAZON CONNECTIVITY

It is vital to safeguard the connectivity of the Amazon. To achieve this, the following actions are essential:

REFERENCE DOCUMENTS

Protecting the connectivity of the Amazon to ensure the future of the planet: The missing piece in the climate conversation

See more

An Amazon Climate Pact - a strategic call by the eight Amazonian states to implement the Belém Declaration and prevent the collapse of one of the planet's climate regulators

See more

THE IMPORTANCE OF COLLABORATION BETWEEN REGIONAL NETWORKS TO SAFEGUARD AMAZON CONNECTIVITY:

See more

LA RELEVANCIA DE LA ARTICULACIÓN ENTRE REDES REGIONALES PARA SALVAGUARDAR LA CONECTIVIDAD AMAZÓNICA:

THE PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN RAISG AND THE NORTH AMAZON ALLIANCE

Decades of experience have shown that in order to protect the integrity of the Amazon, we must unite efforts, knowledge, and resources. The dynamics of destruction threatening these territories have a regional nature and therefore require regional solutions. In response, civil society organizations have come together to strengthen coordinated action and amplify the impact of collective efforts. For this reason, the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG) and the North Amazon Alliance (ANA)—two regional networks that bring together the expertise of members with more than four decades of direct engagement in territories throughout the basin—work hand in hand to fulfill a shared vision: protecting the integrity of the Amazon through complementary perspectives.

RAISG, a regional network specializing in the generation of high-quality information, joins forces with ANA for the sake of connectivity. ANA is a coalition of civil society organizations that, for more than three decades, have developed territorial processes in close collaboration with Indigenous Peoples and local communities. They share the mission of safeguarding connectivity in its ecological, social, and cultural dimensions. This alliance has strengthened a common voice, fostered regional frameworks for action, and generated inputs that inform decision-making by governments, Indigenous and local community organizations, donors, and other strategic actors across the region.

This collaboration between the two networks extends an open invitation for others to join this shared purpose—bringing their own visions, expertise, and actions—under the conviction that it is only possible to protect the diversity that sustains life by embracing the diversity that defines us, and by reinforcing the networks of relationships that make us stronger. The collaborative partnership between ANA and RAISG highlights the importance of approaching the Amazon as a single, interconnected system— a unit sustained by its diversity. Their complementary visions and joint actions not only reinforce the perspective of connectivity presented in this study, but also lay the groundwork for deeper and more effective collaboration in the years to come.

LET'S CONNECT THE AMAZON

LET'S JOIN FORCES TO SAFEGUARD THIS TERRITORY TOGETHER

Technical development of the study:

Adriana Rojas

David Santiago Afanador

Nestor Raúl Espejo

Conceptual and narrative development and editing:

Angélica García

Felipe Samper

Mariana Gómez Soto

Illustration and design:

Camila Arboleda

Programming:

Diego Meneghetti